League was conceived in all seriousness as a forum for playing invented games and sports. (Note: next play date is Sunday 30 December.) Why this focus on play, you ask? Isn’t it a frivolous pursuit? This reaction isn’t unexpected. On one hand play might be dismissed a useless luxury, and on the other it could be characterized as trifling because of its concern with rules.

Yet on the contrary, many have argued that play is a fundamental human impulse, even one of our highest achievements. Thinkers from the realms of psychology, philosophy, sociology, anthropology, education, and theology, have argued for the importance of play. Their varied defenses of play do not deny the characterizations of play as both free and rule-bound, and in fact argue that these properties are part of what makes play one of the great human goods.

Play is fundamentally tied to human culture

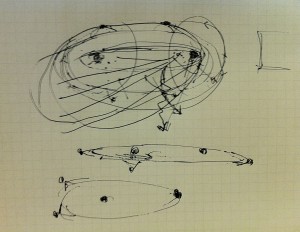

In an important early definition of play, Johan Huizinga identified play as free and set apart from ordinary life, a sacred activity that unfolds within a delimited sphere — the “magic circle” of play. Play creates and respects order, is utterly absorbing for players, and is unrelated to material interest.(1) With these characteristics of freedom and order, play precedes — and indeed is one of the conditions that generates — human culture. “Civilization is, in its earliest phases, played. It does not come from play(…) it arises in and as play, and never leaves it.”(2)

Anthropologist Roger Caillois buit on Huizinga’s work, describing play as “an occasion of pure waste: waste of time, energy, ingenuity, skill, and often of money.”(3) Yet play is an essential component of human society; many social structures and behaviours can be viewed as forms of play. Caillois outlined fundamental forms of play, each of which also range between structured and spontaneous: games of chance, role playing, competition, and vertigo (altered perception). These forms of play tend to be institutionalized within societies: for instance, games of chance take cultural form in lotteries, institutional from as the stock market, or appear corrupted in the form of superstitions. Play is embedded throughout human culture.

Play is an ultimate human goal

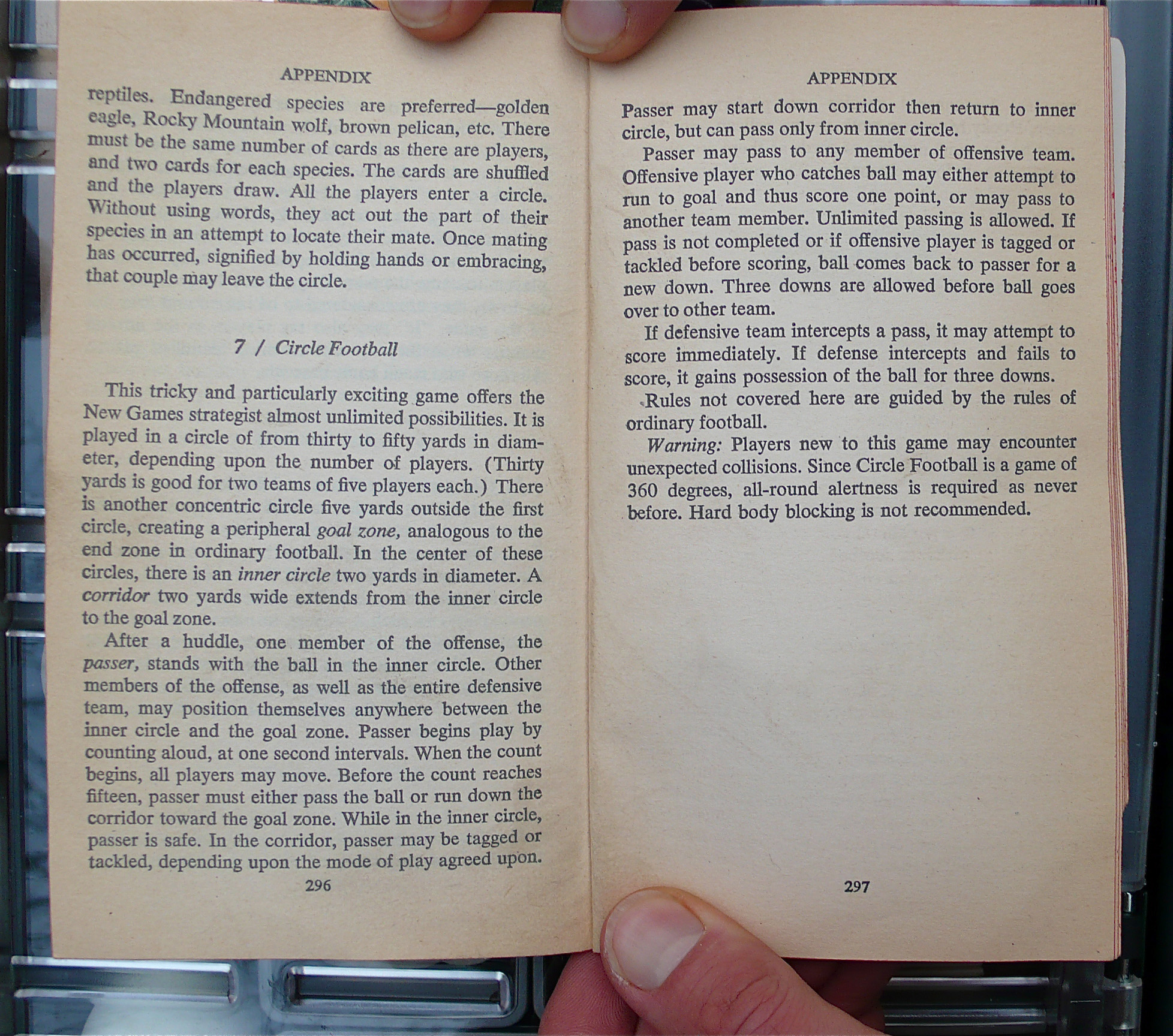

Some might wish to dismiss play as inconsequential because it is constrained by rules. Yet in the philosophical work The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia, Bernard Suits undertakes to define what a game is, and finally concludes that play is central to human ideals, and thus to any conception of Utopia. Suits provides the very useful definition that “playing a game is a voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles”(4) and a “lusory attitude” as a psychological will to accept rules in order to enter a state of play. It is the voluntary acceptance of limitations — the uncoerced freedom of play — that marks its exalted nature. In Utopia, we would be free to play.

Play is central to a meaningful life

Is luxury really the best way to characterize play? Since Aristotle, happiness has often been thought of as an ultimate goal of humans. However, as Mihály Csíkszentmihályi elaborates, it is not material luxuries that produce happiness or satisfaction, but rather the cultivation of conditions of “optimal experience.”(5)

In his primary work Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, Csíkszentmihályi describes states of flow in the realms of physical activity, ritual, thought, creative play, and work. These are all activities that, like games, involve action within rules. “What makes these activities conducive to flow is that they were designed to make optimal experience easier to achieve. They have rules that require the learning of skills, they set up goals, they provide feedback, they make control possible. They facilitate concentration and involvement by making the activity as distinct as possible from(…) everyday existence.”(6) Certainly, these activities also can be pursued without attaining a state of flow, but the implications of Csíkszentmihályi’s arguments are that flow is important for these activities to feel meaningful.

A psychologist largely concerned with questions of creativity and joy, Csíkszentmihályi outlines flow as a satisfying state of concentration, engagement and absorption in an activity. Importantly, to achieve a state of flow requires a balance — play, in other words — between challenge and skill: “a sense that one’s skills are adequate to cope with the challenges at hand, in a goal-directed, rule-bound action system that provides clear clues as to how well one is performing. Concentration is so intense that there is no attention left over to think about anything irrelevant, or to worry about problems. Self-consciousness disappears, and the sense of time becomes distorted. An activity that produces such experiences is so gratifying that people are willing to do it for its own sake, with little concern for what they will get out of it, even when it is difficult, or dangerous.”(7)

Play is transformative

Poet Diane Ackerman builds on Csíkszentmihályi’s concept of flow. Ackerman sees the possibility of “deep play” in myriad human endeavours, including experiences in face of nature, during extreme pursuits, in dramatically isolated situations, and working with language. “Deep play arises in such moments of intense enjoyment, focus, control, creativity, timelessness, confidence, volition, lack of self-awareness (hence transcendence), while doing things intrinsically worthwhile, rewarding for their own sake, following certain rules (they may include the rules of gravity and balance), on a limited playing field. Deep play requires one’s full attention.”(8)

Importantly, though, these activities are not categorically playful, but rather deep play is a state of absorption in a situation irrespective of its character. It is ecstatic, rapturous experience. “Deep play is the ecstatic form of play. In its thrall, all the play elements are visible, but they’re taken to intense and transcendent heights. Thus deep play should really be classified by mood, not activity. It testifies to how something happens, not what happens. Games don’t guarantee deep play, but some activities are prone to it: art, religion, risk-taking, and some sports”.(9)

Ackerman describes deep play in terms approaching religious, making clear that the transformative experiences she’s talking about have little to do, or are even impeded by, the proscribed habits of religion, although ritual delimitation is part of what creates the sacred space of play. “For humans, play is a refuge from ordinary life, a sanctuary of the mind, where one is exempt from life’s customs, methods, and decrees. Play always has a sacred place— some version of a playground — in which it happens. The hallowed ground is usually outlined, so that it’s clearly set off from the rest of reality. This place may be a classroom, a sports stadium, a stage, a courtroom, a coral reef, a workbench in a garage, a church or temple, a field where people clasp hands in a circle under the new moon. Play has a time limit, which may be an intense but fleeting moment, the flexible innings of a baseball game, or the exact span of a psychotherapy session.”(10)

Play connects us with great ideas

Theologian Michael Novak has also written of the great passions that we are willingly drawn into when engaged with sports in particular. Novak explains the impulse to play and follow sports in terms of their conversation with ritual. “Even in our own secular age and for quite sophisticated and agnostic persons, the rituals of sports really work. They do serve a religious function: they feed a deep human hunger, place humans in touch with certain dimply perceived features of human life within this cosmos, and provide an experience of at least a pagan sense of godliness.”(11)

Novak’s classic The Joy of Sports is a convincing exposition on the religious character of sports that is reminiscent of early definitions of play as foundational to culture. “Play is the most human activity. It is the first act of freedom.”(12) “Play is not tied to necessity, except the necessity of the human spirit to exercise its freedom, to enjoy something that is not practical, or productive, or required for gaining food and shelter. Play is human intelligence, and intuition, and love of challenge and contest and struggle; it is respect for limits and laws and rules, and high animal spirits, and a lust to develop the art of doing things perfectly. Play is what only humans truly develop.”(13)

Novak notes that only certain ideologies privilege work over play, and provides an alternate view of play as the ultimate ideal. “Play, not work, is the end of life. To participate in the rites of play is to dwell in the Kingdom of Ends. To participate in work, career, and the making of history is to Labor in the Kingdom of Means.(…) Work, of course, must be done. But we should be wise enough to distinguish necessity from reality. Play is reality. Work is diversion and escape.”(14)

Play is a survival skill

Within Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (in which fundamental physiological and safety needs must be fulfilled before questions of self-esteem), play is one of the concerns that are attended to once basic needs are secured.(15) Or is it? One could argue that strategic thinking and competition are survival skills, as we see in the branch of economics known as game theory. Problem-solving, socialization and learning through play are also recurrent themes of childhood development theories. Indeed, as Caillois described, play extends to many aspects of human activity.

Tellingly, animals also play. “Evolutionary psychologists believe that there must be an important benefit of play, since there are so many reasons to avoid it. Animals are often injured during play, become distracted from predators, and expend valuable energy.” The evolving theory is that play helps animals prepare to survive in their own particular environments.(16) The parallel to children developing motor- and social skills seems obvious.

Play is pervasive

As computer gaming becomes ubiquitous, as video games become the dominant form of entertainment in contemporary society, and as game design has become big business, it seems ever more pressing to understand the compulsions and potential of play. Experimental game designer Frank Lantz succinctly summarizes the promise of games: “Games can inspire the loftiest form of cerebral cognition and engage the most primal physical response, often simultaneously.(…) Games are capable of addressing the most profound themes of human existence in a manner unlike any other form of communication — open-ended, procedural, collaborative; they can be infinitely detailed, richly rendered, and yet always responsive to the choices and actions of the player.”(17)

We have reached a point where games are approaching ubiquity, a point where businesses are looking to “gameify” their offerings in order to attract consumers and cash in on those compulsions.(18) Given the pervasiveness of gaming, Lantz states simply why it is important to take play seriously, to push for the best that play can be: “If enough people believe that games are meant to be mindless fun, then this is what they will become. If enough people believe that games are capable of greater things, then they will inevitably evolve and advance.”(19)

Play can do good

We see, then, that there is a long tradition of believing in the good of games and play. Understanding the power of games, there is also emerging a domain of critical game design that takes the social practices of gaming seriously. Game designer Jane McGonigal is concerned with alternate-reality games intended to improve real life, with “pervasive games” that use game imagery to disrupt the conventions of public space, and with ubiquitous computing that imagines game-like interactivity in the real world. She has argued for the collective intelligence of online computer gaming as a powerful engine for solving problems, human evolution, co-operation and trust, producing optimism, and creating meaning. McGonigal goes so far as to say that “playing games is the single most productive way we can spend our time.” Her book Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World argues that game mechanics, particularly of massively collaborative projects, can be harnessed to make the real world a better place.(20)

It is uncertain whether the types of game that McGonigal proposes will ultimately prove compelling enough to generate continued play. And as play practices evolve and the social stakes are raised, we certainly should ask what games can accomplish, what good they might bring about. But fundamentally, play in itself is a good. Why do we play? Because it is part of what makes us human.

Germaine Koh

Vancouver, December 2012 (21)

Playing “Wicket Awesome” at League

Notes

1. Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: a study of the play element in culture, original Dutch 1938 (Boston: Beacon, 1955), pp. 8-13.

2. Huizinga, p.173.

3. Roger Caillois, Man, Play and Games, original French 1958, trans. 1961 (Chicago: University of Illinois, 2001), p. 5-6.

4. Bernard Suits, The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia, original 1978 (Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview, 2005), p. 55.

5. Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (New York: HarperCollins, 1990), p. 1-3.

6. Csíkszentmihályi, p. 72.

7. Csíkszentmihályi, p. 71.

8. Diane Ackerman, Deep Play (New York: Vintage, 1999), p. 188.

9. Ackerman, p. 12.

10. Ackerman, p. 6.

11. Michael Novak, The Joy of Sports: End Zones, Bases, Baskets, Balls, and the Consecration of the American Spirit (New York: Basic Books, 1976), p. 20.

12. Novak, p. 32.

13. Novak, p. 33.

14. Novak, p. 40.

15. “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs”, Wikipedia, saved 28 December 2012, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maslow%27s_hierarchy_of_needs.

16. “Play and Animals” in “Play (activity)”, Wikipedia, saved 28 December 2012, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Animal_play#Play_and_animals.

17. Frank Lantz, “Foreword” in Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals, MIT Press, 2003), p. x.

18. Nick Wingfield, “All the World’s a Game, and Business Is a Player”, New York Times, 23 December 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/24/technology/all-the-worlds-a-game-and-business-is-a-player.html?hp&_r=0.

19. Lantz, p. xi.

20. Promotion at http://realityisbroken.org for Jane McGonigal, Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World (Penguin, 2011).

21. Thanks to Ian Verchere for reading and editing.

That brings to mind the slide installed at the Overvecht train station in Utrecht.

That brings to mind the slide installed at the Overvecht train station in Utrecht.