A bunch of projects crossed our desk recently that are all about re-imagining the potential of urban space.

1.

Walking East

First off, here’s a project that is underway right now, for an undetermined length of time — perhaps a few days, perhaps more. One of our own, Jay White started out from downtown Vancouver yesterday, November 28, on a long, rule-based walk. You could help him along in some way by giving him a call at 1-778-319-2405.

This is the second of a series of walks he plans to undertake, heading eastwards from downtown Vancouver, according to certain rules, which in this case are:

- Start at Emily Carr University and walk Eastwards.

- When I don’t know which route is more East, choose between them completely randomly.

- A route can be any linear trace created by human and/or non-human: road, sidewalk, deer trail, stream bank, ridgeline, gully.

- Do not knowingly trespass.

- Buy food along the way, but do not stray from the random route to buy food.

- The walk ends when I miss a meal or become exceedingly uncomfortable.

In the first walk he did, he experienced a new connection to, but also estrangement from, the familiar urban environment:

In the first walk, I was struck by the vastly different perspective I had of an area that I’ve lived in for so long. I was also struck by the complete distance I felt from the people in my vicinity, and of my inability to share what I was experiencing in an immediate, direct and personal way. So this time around, I am inviting you to give me a phone call.[...] My cellphone number is 778-319-2405. No pressure!

He also reflected upon what he is ‘accomplishing’ through the walks.

The walks have a variety of meanings for me: They are an excuse to get outside, a means to use my whole body and mind to learn, to come to new understandings of the landscape and the beings that surround me. I’m also seeing it as a part of my art practice, as a means to create art, as art in itself, and as a program of research[...]. Above all, it is something I enjoy more than I ever would have imagined.

It’s a brave idea, putting oneself into a vulnerable situation in order to bear witness to the collective landscape. The project has all kinds of potential for observing transitions in how space is used as one moves from a dense urban landscape into suburban and then agrarian ones: a kind of moving through time and models of social organization as well as through space.

2.

Dude Chilling Park

In other Vancouver news, last week another citizen took it into his own hands to help reshape our public space in the name of how it’s actually used. One day a new, seemingly official, Park Board sign appeared in a modest East Van park, renaming it from Guelph Park to “Dude Chilling Park.” The Vancouver Province reported on it, gamely describing the park as “a place where dudes and dudettes can presumably go to, you know, just chill — like the relaxed figure depicted in a sculpture on the park’s grass.” Apparently Park Board vice-chair Aaron Jesper praised the handiwork of the counterfeiter(s), and the Province‘s polling of passers-by also revealed acceptance of the new moniker: “Wendy Stewart, who takes a lunchtime walk around the park every day, was also surprised by the sudden renaming. Given the park serves as a hangout for the homeless, she thinks the renaming might be a form of social commentary. ‘You can see them there, sitting on the bench — they don’t have much,’ she said, adding a lot of families also come to the park to chill. ‘Dudes chilling is OK.’”

Then came the social media campaign. People posted pictures, and a dude named Dustin Bromley started a change.org petition to Mayor Gregor Robertson, to permanently change the park’s name, arguing that it has been “under appreciated, and mostly occupied by empty bottles of mouthwash”, but that could become a destination. Within a few days, the petition had gained 1500 signatures, and the fate of Dude Chilling is now being debated in local and social media. (We sent a suggestion that it could come live in the yard of the League field house in Elm Park.) According to Park Board commissioner Sarah Blyth, it’s on the agenda for the Park Board’s December 10 meeting.

It turns out that the sign was the work of artist Viktor Briestensky, as the Province reported in a follow-up article.

Whatever the eventual fate of Dude Chilling, it succeeded in playfully reminding us that we could all have a part in shaping public space into the forms we’d like, that communal space comes to have its own meanings through use, and that there’s nothing fixed about the space around us.

3.

Improv Everywhere, “Black Friday Dollar Store”

New York City “prank collective” Improv Everywhere was at it again on Black Friday. Masters of twisting expectations and disrupting habits in urban space, this time they had 100 people camp out in front of a 99-cent store in the early morning of Black Friday, the biggest retail sales day of the year in the United States. “When the store opened, the crowd rushed inside and made purchases, buying 99 cent items with glee. Actress Cody Lindquist posed as a local NBC news reporter and conducted interviews with confused and delighted store employees and passersby.”

Thank you, Improv Everywhere, for creating one joyfully absurd moment to balance the make-you-despair-of-humanity stories of consumer greed that are otherwise the annual Black Friday news fare.

4.

Urban transit

Inhabitat reports on a prototype trampoline sidewalk “built by Estonian firm Salto Architects for the Archstoyanie Festival this summer in Russia. During the festival Fast Track was used for both play and transport, giving visitors a different way to get from one place to another.”

That brings to mind the slide installed at the Overvecht train station in Utrecht. As described last year by the Pop-Up City blog, “the slide offers travellers the opportunity to quickly reach the railway tracks when they’re in a hurry. But above all, the slide is a great instrument to make the city more playful. The ‘transfer accelerator’ was designed by Utrecht-based firm HIK Ontwerpers, and installed as the final piece of the renovation of the Overvecht railway station.”

That brings to mind the slide installed at the Overvecht train station in Utrecht. As described last year by the Pop-Up City blog, “the slide offers travellers the opportunity to quickly reach the railway tracks when they’re in a hurry. But above all, the slide is a great instrument to make the city more playful. The ‘transfer accelerator’ was designed by Utrecht-based firm HIK Ontwerpers, and installed as the final piece of the renovation of the Overvecht railway station.”

5.

Chair-bombing

Here’s a project by Brooklyn collective DoTank, who are working to improve the commons through “tactical urbanism” projects. It’s a sort of recipe for improving the livability of public space.

Chair-bombing is the act of building chairs out of found materials, and placing those chairs in a public space in order to improve its comfort, social activity, and sense of place.

DoTank’s chair-bombing process began by building adirondack chairs made from discarded shipping pallets. The DIY chairs were placed in public areas that were in need of street furniture. These places included sidewalks in front of coffee shops, transit stops with no seating, and other areas with potential to become quality public spaces, but were suffering from a dearth of public amenities.

[Thanks to Maia and Andreas from Grey Sky Thinking for the lead.]

6.

Toshiko Horiuchi MacAdam

ArchDaily posted a profile of artist Toshiko Horiuchi MacAdam, who makes brightly coloured, hand-knit installations and public spaces. Inspired by natural architectural forms and her own background as a textile designer, her practice has developed through a sensitive observation of materials and forces. Her approach sounds like play: “Most of my artwork involves architectural ideas or references. I am interested in how form is created through tension and the force of gravity including the weight of the material itself and textile structures. It is the intersection of art and science – like geometry – which we observe in nature. ”

[Thanks to architect Carla Smith for the lead. Go check out her coaching project Roller Derby Athletics.]

7.

9-Man

And lastly, here’s a Kickstarter campaign for 9-Man, a feature documentary directed by Ursula Liang, about an extremely localized street version of volleyball played in Chinatowns since the 1930s. Playing against stereotypes and segregation of Asians, it was a game that developed in isolation within large cities.

9-MAN is a streetball game played in Chinatown by Chinese-American and Chinese-Canadian men. It’s fast, chaotic, unpredictable, grueling; the rules are distinct and exist no where else in the world—imagine volleyball with 18 guys, dunks, and bloodied elbows. This is a sport that is completely unique to Chinese-Americans and therefore something very special to those who play it. Why haven’t you heard of it? Because it’s played only by men. And two-thirds of the players have to be “100% Chinese”. And perhaps because good things are often kept secret. If you’re not part of the 9-man community, you may have no idea what an incredible scene it is. We’re trying to change that.

The documentary promises to reveal something of the particular social conditions that this particular sport grew out of. If you want to help the film get made, head over to their Kickstarter page before December 21 to give them a hand.

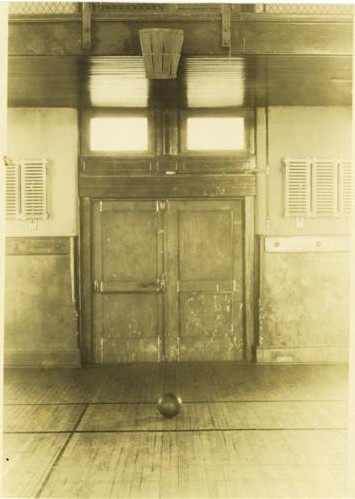

We might forget sometimes that even our best-known games and sports have not always existed the way they are now; they either evolved over time or through cultural exchange, or they were created wholesale. Basketball, a sport now played by 200 million worldwide, was invented in late 1891 by James Naismith as a challenge from the YMCA Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts, to create a sport for the school’s most incorrigible students that would be “interesting, easy to learn, and easy to play in the winter and by artificial light.”[1]

We might forget sometimes that even our best-known games and sports have not always existed the way they are now; they either evolved over time or through cultural exchange, or they were created wholesale. Basketball, a sport now played by 200 million worldwide, was invented in late 1891 by James Naismith as a challenge from the YMCA Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts, to create a sport for the school’s most incorrigible students that would be “interesting, easy to learn, and easy to play in the winter and by artificial light.”[1] Cadavre Exquis (Exquisite Corpse). Invented (or re-imagined) by the Surrealist group around the 1920s, Cadavre Exquis was first a language-based parlour game in which different people wrote elements of a sentence without seeing the other participants’ contributions. The first sentence produced —”The exquisite corpse will drink the new wine.”— gave the game its name. Later it evolved into a drawing game. Like many Surrealist techniques such as automatic writing and collage, the game attempts to disrupt traditional patterns and conventional thoughts about authorship.

Cadavre Exquis (Exquisite Corpse). Invented (or re-imagined) by the Surrealist group around the 1920s, Cadavre Exquis was first a language-based parlour game in which different people wrote elements of a sentence without seeing the other participants’ contributions. The first sentence produced —”The exquisite corpse will drink the new wine.”— gave the game its name. Later it evolved into a drawing game. Like many Surrealist techniques such as automatic writing and collage, the game attempts to disrupt traditional patterns and conventional thoughts about authorship. Yoko Ono. The Fluxus group with which Ono was associated, created many critical games that played with rules and chance operations. Although not obviously games, Ono’s work is particularly devastating when thought of in those terms, for they directly address the implicit rules by which we interact with each other. Take for example, her 1964 performance piece, Cut Piece, in which the audience was invited to the stage one by one to cut off and keep a piece of her clothing. She also made an all-white chess set (1966) and a series of works consisting simply of plain but socially challenging instructions, such as “Touch each other” or “Scream. 1. against the wind 2. against the wall 3. against the sky.”

Yoko Ono. The Fluxus group with which Ono was associated, created many critical games that played with rules and chance operations. Although not obviously games, Ono’s work is particularly devastating when thought of in those terms, for they directly address the implicit rules by which we interact with each other. Take for example, her 1964 performance piece, Cut Piece, in which the audience was invited to the stage one by one to cut off and keep a piece of her clothing. She also made an all-white chess set (1966) and a series of works consisting simply of plain but socially challenging instructions, such as “Touch each other” or “Scream. 1. against the wind 2. against the wall 3. against the sky.” Gustavo Artigas, The Rules of the Game, San Diego/Tijuana, 2000-01. A project for the cross-border project insite, it included an event in which two Mexican football teams and two American basketball teams played against each other on the same court at the same time. Although not the first artist to propose a game involving two balls (see Uri Tzaig, for example), the literal clash of cultures staged by Artigas brought to the fore questions of cultural habits embedded in games.

Gustavo Artigas, The Rules of the Game, San Diego/Tijuana, 2000-01. A project for the cross-border project insite, it included an event in which two Mexican football teams and two American basketball teams played against each other on the same court at the same time. Although not the first artist to propose a game involving two balls (see Uri Tzaig, for example), the literal clash of cultures staged by Artigas brought to the fore questions of cultural habits embedded in games. Lee Walton has created many performances that cross the systems of sport with urban systems and spaces, turning the city into a space of play. For example, for

Lee Walton has created many performances that cross the systems of sport with urban systems and spaces, turning the city into a space of play. For example, for

Big Urban Game, by Katie Salen, Nick Fortuno and Frank Lantz (2003). The B.U.G. project was commissioned by the University of Minnesota Design Institute as part of a process of looking at urban planning for Minneapolis-Saint Paul. Three teams moved large, inflatable game pieces through the Twin Cities, taking advice online advice from the public to determine the fastest route. As Lantz writes about games that cover a large area, played by large numbers of people, set in the real world, they tend to “distort the relationship between game worlds and real worlds.”[4]

Big Urban Game, by Katie Salen, Nick Fortuno and Frank Lantz (2003). The B.U.G. project was commissioned by the University of Minnesota Design Institute as part of a process of looking at urban planning for Minneapolis-Saint Paul. Three teams moved large, inflatable game pieces through the Twin Cities, taking advice online advice from the public to determine the fastest route. As Lantz writes about games that cover a large area, played by large numbers of people, set in the real world, they tend to “distort the relationship between game worlds and real worlds.”[4]