A roundup of interesting projects and issues that recently crossed our desk. 1. Below the Belt from Vimeo user jiann Below The Belt is an interactive installation exploring the tensions between competitive contact sports and the inward focus of breathing

Games and critical invention

“What do you mean by invented sports and games,” you may ask. My own view is that play is at heart about invention, testing, and improvisation — potentially radical processes which can be lost when games become very regulated.

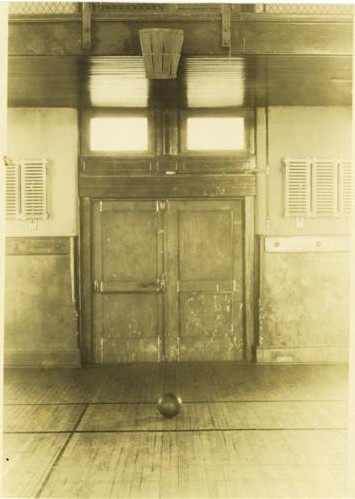

We might forget sometimes that even our best-known games and sports have not always existed the way they are now; they either evolved over time or through cultural exchange, or they were created wholesale. Basketball, a sport now played by 200 million worldwide, was invented in late 1891 by James Naismith as a challenge from the YMCA Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts, to create a sport for the school’s most incorrigible students that would be “interesting, easy to learn, and easy to play in the winter and by artificial light.”[1]

We might forget sometimes that even our best-known games and sports have not always existed the way they are now; they either evolved over time or through cultural exchange, or they were created wholesale. Basketball, a sport now played by 200 million worldwide, was invented in late 1891 by James Naismith as a challenge from the YMCA Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts, to create a sport for the school’s most incorrigible students that would be “interesting, easy to learn, and easy to play in the winter and by artificial light.”[1]

Game design and sports have also become big business, so it can be easy to overlook the critical potential of play. Theorists of play have defined it variously as an activity that stands apart from ordinary life, as activity that involves the free acceptance of binding rules, as a cultural expression of a society, and so on. Games always seem to emerge in relation to a system, and so it follows that play can be a potential tool for subverting expectations and conventions. Artists have understood this well, and over the years have invented many games

that involve a radical rethinking of existing systems.

Some critical games

- Anti-Monopoly. In 1974 economics professor Ralph Anspach invented a board game resembling Monopoly, but re-written with language that undermined the cultural idea of monopoly upon which the original was based. Similarly, Bertel Ollman’s 1978 game Class Struggle, reworked the original, proposing instead to help players “prepare for life in capitalist America.”[2]

Cadavre Exquis (Exquisite Corpse). Invented (or re-imagined) by the Surrealist group around the 1920s, Cadavre Exquis was first a language-based parlour game in which different people wrote elements of a sentence without seeing the other participants’ contributions. The first sentence produced —”The exquisite corpse will drink the new wine.”— gave the game its name. Later it evolved into a drawing game. Like many Surrealist techniques such as automatic writing and collage, the game attempts to disrupt traditional patterns and conventional thoughts about authorship.

Cadavre Exquis (Exquisite Corpse). Invented (or re-imagined) by the Surrealist group around the 1920s, Cadavre Exquis was first a language-based parlour game in which different people wrote elements of a sentence without seeing the other participants’ contributions. The first sentence produced —”The exquisite corpse will drink the new wine.”— gave the game its name. Later it evolved into a drawing game. Like many Surrealist techniques such as automatic writing and collage, the game attempts to disrupt traditional patterns and conventional thoughts about authorship. Yoko Ono. The Fluxus group with which Ono was associated, created many critical games that played with rules and chance operations. Although not obviously games, Ono’s work is particularly devastating when thought of in those terms, for they directly address the implicit rules by which we interact with each other. Take for example, her 1964 performance piece, Cut Piece, in which the audience was invited to the stage one by one to cut off and keep a piece of her clothing. She also made an all-white chess set (1966) and a series of works consisting simply of plain but socially challenging instructions, such as “Touch each other” or “Scream. 1. against the wind 2. against the wall 3. against the sky.”

Yoko Ono. The Fluxus group with which Ono was associated, created many critical games that played with rules and chance operations. Although not obviously games, Ono’s work is particularly devastating when thought of in those terms, for they directly address the implicit rules by which we interact with each other. Take for example, her 1964 performance piece, Cut Piece, in which the audience was invited to the stage one by one to cut off and keep a piece of her clothing. She also made an all-white chess set (1966) and a series of works consisting simply of plain but socially challenging instructions, such as “Touch each other” or “Scream. 1. against the wind 2. against the wall 3. against the sky.” Gustavo Artigas, The Rules of the Game, San Diego/Tijuana, 2000-01. A project for the cross-border project insite, it included an event in which two Mexican football teams and two American basketball teams played against each other on the same court at the same time. Although not the first artist to propose a game involving two balls (see Uri Tzaig, for example), the literal clash of cultures staged by Artigas brought to the fore questions of cultural habits embedded in games.

Gustavo Artigas, The Rules of the Game, San Diego/Tijuana, 2000-01. A project for the cross-border project insite, it included an event in which two Mexican football teams and two American basketball teams played against each other on the same court at the same time. Although not the first artist to propose a game involving two balls (see Uri Tzaig, for example), the literal clash of cultures staged by Artigas brought to the fore questions of cultural habits embedded in games. Lee Walton has created many performances that cross the systems of sport with urban systems and spaces, turning the city into a space of play. For example, for City Golf (2002), a round of golf was played in the city of San Francisco as if the golf course were superimposed onto the city. The score for each hole required a (social) reward or penalty of different degree to be performed.

Lee Walton has created many performances that cross the systems of sport with urban systems and spaces, turning the city into a space of play. For example, for City Golf (2002), a round of golf was played in the city of San Francisco as if the golf course were superimposed onto the city. The score for each hole required a (social) reward or penalty of different degree to be performed. The Game at Hand, by Larry and Debby Kline (2002). A hand-made chess set in which one side features icons of American culture, and the other an indistinguishable set of burqa-clad figures. As the artists describe, “As viewers are encouraged to play, it becomes evident that the game cannot be conducted fairly even with the most conscientious of intentions. Once engaged, players become quickly confused; the player controlling the US side of the board cannot adequately strategize and the opponent will eventually violate the rules of the game either knowingly or unknowingly.“[3]

The Game at Hand, by Larry and Debby Kline (2002). A hand-made chess set in which one side features icons of American culture, and the other an indistinguishable set of burqa-clad figures. As the artists describe, “As viewers are encouraged to play, it becomes evident that the game cannot be conducted fairly even with the most conscientious of intentions. Once engaged, players become quickly confused; the player controlling the US side of the board cannot adequately strategize and the opponent will eventually violate the rules of the game either knowingly or unknowingly.“[3] Big Urban Game, by Katie Salen, Nick Fortuno and Frank Lantz (2003). The B.U.G. project was commissioned by the University of Minnesota Design Institute as part of a process of looking at urban planning for Minneapolis-Saint Paul. Three teams moved large, inflatable game pieces through the Twin Cities, taking advice online advice from the public to determine the fastest route. As Lantz writes about games that cover a large area, played by large numbers of people, set in the real world, they tend to “distort the relationship between game worlds and real worlds.”[4]

Big Urban Game, by Katie Salen, Nick Fortuno and Frank Lantz (2003). The B.U.G. project was commissioned by the University of Minnesota Design Institute as part of a process of looking at urban planning for Minneapolis-Saint Paul. Three teams moved large, inflatable game pieces through the Twin Cities, taking advice online advice from the public to determine the fastest route. As Lantz writes about games that cover a large area, played by large numbers of people, set in the real world, they tend to “distort the relationship between game worlds and real worlds.”[4]

Notes

- John Fox, The Ball: Discovering the Object of the Game (Harper Perennial, 2012), p. 267-8.

- Mary Flanagan, Critical Play: Radical Game Design (MIT Press, 2009), pp. 87-8.

- Larry and Debby Kline, “The Game at Hand,” http://www.jugglingklines.com/Game_at_Hand.htm.

- Frank Lantz, “Big Games”, http://www.decisionproblem.com/big/

Obscure sports — links

Miscellaneous links to obscure, oddball, and cult sports.

- How Stuff Works, “9 Odd Sporting Events from Around the World“: including Cheese Rolling, Pooh Sticks, and Wife Carrying.

- Listverse, “10 Odd Discontinued Olympic Sports“: in case you thought Tug-of-War was just for kids.

- Matador Network, “10 Odd Sports Around the World“. It’s official: everyone thinks Toe Wrestling is odd.

- The Rough Guide to Cult Sport (London: Rough Guides, 2011). Compendium of sports with dedicated followings, cult sporting figures, and historic battles. Get a taste of some on the Rough Guides site.

- Top End Sports, “Complete List of Weird and Unusual Sports” and “Unusual Sports“.

- World Alternative Games in Llanwrtyd Wells, Wales, best(?) known as the traditional home of the World Bog Snorkelling Championships.