A roundup of interesting projects and issues that recently crossed our desk.

1.

Below the Belt

from Vimeo user jiann

Below The Belt is an interactive installation exploring the tensions between competitive contact sports and the inward focus of breathing practices that support them. Using boxing props embedded with biometric sensors, each ‘competitor’s’ breath is measured according to speed and depth differentials.

[Forwarded by media curator Sarah Cook]

2.

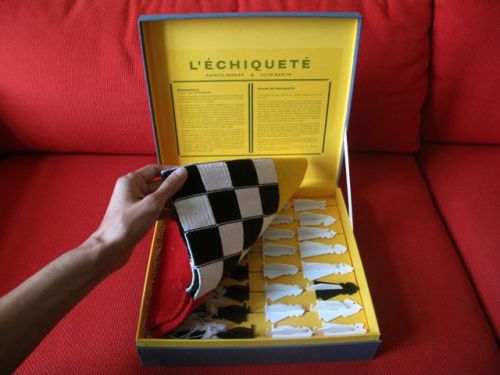

L’Échiqueté (Checkered Chess)

a project by Patrick Bernier and Olive Martin

The pieces move the same way as they do in classical chess, and their starting positions are unchanged, but, as the game progresses, new characters make an appearance! In a nutshell: the capture of an enemy piece produces a piece belonging to both players, a double agent.

Basics.

1. Each capture produces a new piece in place of the two pieces involved. The player executing the capture decides whether this new piece takes on the nature of the capturing or the captured piece.

2. The new piece arising from a capture is neither white nor black but ‘checkered.’

3. All checkered pieces belong to the player currently taking their turn and can capture the opponents pieces (as described in rule 1 above). Their manner of moving remains the same as in classical chess.

See complete rules and more at chess-variants.net

[Forwarded by curator Joseph del Pesco of the Kadist Art Foundation]

3.

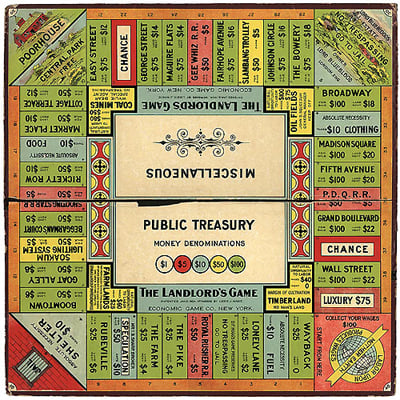

Monopoly Is Theft

By Christopher Ketcham, from Harper’s

Ketcham relates “the antimonopolist history of the world’s most popular board game” — the bickering over intellectual property, with the history of American tax policy as a side story.

The official history of Monopoly, as told by Hasbro, which owns the brand, states that the board game was invented in 1933 by an unemployed steam-radiator repairman and part-time dog walker from Philadelphia named Charles Darrow. Darrow had dreamed up what he described as a real estate trading game whose property names were taken from Atlantic City, the resort town where he’d summered as a child. Patented in 1935 by Darrow and the corporate game maker Parker Brothers, Monopoly sold just over 2 million copies in its first two years of production, making Darrow a rich man and likely saving Parker Brothers from bankruptcy. It would go on to become the world’s best-selling proprietary board game. At least 1 billion people in 111 countries speaking forty-three languages have played it, with an estimated 6 billion little green houses manufactured to date. Monopoly boards have been created using the streets of almost every major American city[...]

The game’s true origins, however, go unmentioned in the official literature. Three decades before Darrow’s patent, in 1903, a Maryland actress named Lizzie Magie created a proto-Monopoly as a tool for teaching the philosophy of Henry George, a nineteenth-century writer who had popularized the notion that no single person could claim to “own” land. In his book Progress and Poverty (1879), George called private land ownership an “erroneous and destructive principle” and argued that land should be held in common, with members of society acting collectively as “the general landlord.”

Magie called her invention The Landlord’s Game, and when it was released in 1906 it looked remarkably similar to what we know today as Monopoly.[...]

[Forwarded by Erin Morissette]

4.

Junkyard Sports

DeKoven is a game designer and “fun theorist” who helped shaped the principles of the New Games movement in favour of non-competitive games.

Junkyard Sports is a book and a project that celebrates the creative enjoyment that can be wreaked with everyday objects. The blog records all sorts of mashups of innovative equipment and action.

5.

The Rules of Basketball: Works by Paul Pfeiffer and James Naismith’s “Original Rules of Basket Ball”

Paul Pfeiffer

Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (08), 2005

Fujiflex digital C print, 60 x 48 in.

Collection Glenn and Amanda Fuhrman NY, Courtesy The FLAG Art Foundation

©Paul Pfeiffer. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

the Blanton Museum of Art

University of Texas at Austin

September 16, 2012 – January 13, 2013

This fall, the Blanton Museum of Art at The University of Texas at Austin presents The Rules of Basketball, an exhibition of works by contemporary artist Paul Pfeiffer, presented in conjunction with a special display of James Naismith’s “Original Rules of Basket Ball” — the 1891 document that outlined the 13 original rules of the game. In a rare union, the exhibition considers the sport from a historical perspective, and, on a more psychological level, explores the phenomena and spectacle that surround it. [...]

Artist Paul Pfeiffer’s body of work on basketball creates a unique counterpart to “The Rules” and provides visitors an opportunity to consider the sport in meaningful new ways. Pfeiffer has worked in the field of video, photography, installation art and sculpture since the late 1990s. Celebrated for his groundbreaking use of digital technologies, Pfeiffer adopts today’s frenetic visual language in order to consider the role that mass media plays in shaping consciousness. In this unprecedented presentation at the Blanton, guest curated by Regine Basha, Pfeiffer’s work will be installed in a dialogue with Naismith’s “Rules.” Through eight photographs and six video installations, the artist re-frames the players, the ball, and the architecture of the arena to underline the sublime potential of the game and its metaphoric undertones. Also on view will be an exciting new video work inspired by Wilt Chamberlain’s 1962 100-point game.[...]

6.

Sergio Romo and the Tim Wakefield Fastball

by Jeff Sullivan from Fangraphs

Two out, bottom of the ninth, Tigers down by one, facing being swept in the World Series. Triple-crown winner Miguel Cabrera, is up, the Tigers’ best bet to get them back into it. Sullivan describes the strategic mastery of Romo’s decision not to throw his best pitch.

The pitch was thrown in a 2-and-2 count. The pitch was a Sergio Romo fastball, instead of a Sergio Romo slider. From the start of the year, according to PITCHf/x, Cabrera had seen 131 fastballs in 2-and-2 counts. Of those, 94 were strikes, and of those strikes, 92 were swung at. It hasn’t been often that Cabrera has been caught looking by a two-strike fastball, but Romo had an inkling.[...]

There was every reason for Cabrera to be expecting a slider. There was every reason for Romo to stick with his slider, because he could afford another ball, and because the slider has been his reliable weapon for years. There was every reason for Posey to call for a slider. And this is where we get into game theory. Because there was every reason for one thing, Sergio Romo saw an opportunity to try another thing. We don’t know how often it would’ve worked, given a million repetitions, but we know how it worked the one time. It ended a World Series.[...]

One comment

Toggle Comments