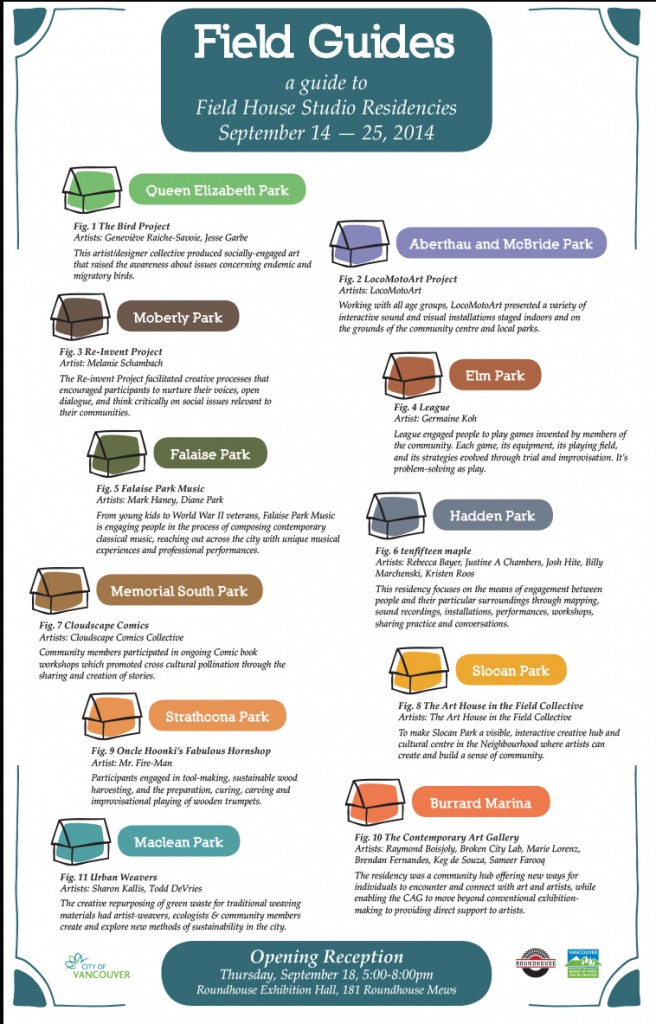

League updates

After an impromptu off-season, League has three events in April.

- Saturday 12 April, 2-4 pm — League play at Satellite Gallery for Canadian Art Gallery Hop

- Sunday 27 April, noon-2 pm — League play day in Elm Park

- Tuesday 29 April, 7pm — PushupKucha, our brand-new short presentation format. Stay tuned for more.

Over the past couple months, we’ve been running play workshops for groups and working with Simon Fraser University student Louise Rusch. Below is the first of a few pieces of her research that Louise will be sharing with us here. This includes some reflections on the game of tag arising from our January play day. One of the games that emerged that day was an ongoing game of tag, marked by the passage of a toy medal. From now on, the person in possession of the medal at the end of each League event is It until the next one. Jay is currently It.

Over the past couple months, we’ve been running play workshops for groups and working with Simon Fraser University student Louise Rusch. Below is the first of a few pieces of her research that Louise will be sharing with us here. This includes some reflections on the game of tag arising from our January play day. One of the games that emerged that day was an ongoing game of tag, marked by the passage of a toy medal. From now on, the person in possession of the medal at the end of each League event is It until the next one. Jay is currently It.

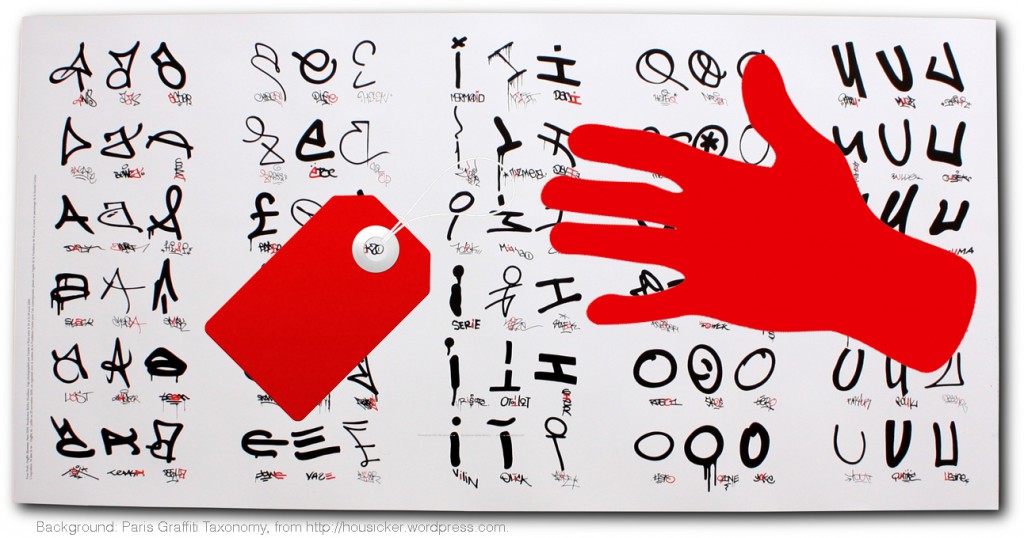

Noodle fencing, from League tag day

Studying Tag

by Louise Rusch

Arts & Culture Studies student, Simon Fraser University

Notes following League Tag day

The theme for League this month was tag – a game of chase. In tag, someone is “it”, and they need to chase others, and either transfer their “it” status to the person they tag, or continue to be “it”. The simplistic structure allows for an infinite number of variations of the game, depending on the space, props, group dynamics, number, and age of the people involved.

From a physical literacy perspective, tag is about learning to self monitor and control your body in motion and space. Players practice the skills of agility, efficiently moving from a resting to a sprinting mode and building stamina for the long chase.

From a cognitive context, tag is about being chased or chasing, strategically considering the skill of balancing and shifting between defensive and offensive position, often simultaneously. During the League session we explored this idea when we did team fencing bouts with long foam noodles in the tennis courts. One team would often single out one player and try to create an opportunity for a quick side tag of the other opponent using speed, control of the noodle, and surprise.

Socially, tag is about power dynamics, especially around the concept of being “it.” Is “it” a desirable place because you want to be the centre of attention? Because you have the confidence to know your place in the group and can easily assess who may or may not be your equal? If you are playing team tag do you have the experience and skill to both keep yourself active in the game and also be a support to your team members?

In Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman’s book Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals, they cite Chris Crawford as stating that all games are a system of conflict and that, paradoxically, it is the staged conflict found in games that makes the play meaningful. Thus playing games is also playing with (dis)comfort with conflict situations (Salen & Zimmerman 250). Later they also note that the simplicity of being either hunted or hunter leaves no room for ambiguity, and that this simplicity is part of the appeal (317).

Historically, “it”ness was attached to illnesses like the plague, thus being less than desirable. Transferred into a game situation, this undesirable state of social isolation is what motivates the “it” person to find someone to tag, which also extends the momentum of the game.

Emotionally, tag tackles the concept of winning and losing, and of being singled out from the group. “It” might represent a place of fear that one will not have the skills to successfully complete a tag.

There have been recent controversies about letting children play tag. These centre on tag as an elimination game, older children dominating the game, the potential of one child being victimized as the “it” person, and the ramifications this might have on self-esteem.

Play theorists often connect tag to rough and tumble play. Anthony Pellegrini reported in a 1995 study on rough and tumble play, that as children enter school age the similarities between “hit at” and “tag a peer” allow for an easy transition into games with a more cooperative structure. He notes that as children get older, rough and tumble play is more likely to be about dominance and related to negative social behaviour (Pellegrini 121).

In terms of formal studies of tag, a study entitled “The ‘It’ Role in Children’s Games,” by clinical psychologist Dr Paul V. Gump and play theorist Brian Sutton-Smith, focused on two different types of “it” games. “It” games were chosen because they are so common in children’s play, and they define specific roles for the players. Power, seen as separate from player skill, was defined as having the ability to choose when the competitive encounter would begin and which kind of play would be chosen for the chase. One game was defined as a low-power because the “it” did not have a lot of control in the game, while the other high-powered “it” game allowed for more control. The research tested the assumptions that high-powered “it” games were more successful generally for players, and especially for unskilled players. Forty boys between seven and ten were tested in advance for athletic ability, to ensure that unskilled players were not needlessly put in positions that would be discouraging for the players or create boredom for the group (390-3).

The results indicated that the low power game was most discouraging for unskilled players and more likely to encourage the group of other boys to behave inappropriately to the “it” person. Often the unskilled player would try to avoid these games before they started. Successful players in either game possessed athletic ability, a sense of power, used strategy, and had “personality factor,” defined as drive or perseverance (395). It was felt that unskilled players were more likely to be successful in games that included an element of chance. I thought the comment about the correlation between skill and chance was interesting, and it corresponds to my own observations from my work (in the field of recreation). I also thought it was interesting that in the low-power games, not only was the “it” person not having a good time, but the other boys also seemed more likely to taunt him (394-7). This speaks to the reality that, without being good or bad, games can have a darker side.

References:

- Gump, P.V. & Sutton-Smith, B. “The ‘It’ Role in Children’s Games.” Avedon, Elliott M. & Sutton-Smith, Brian. The Study of Games. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1971. pp. 390-398.

- Pellegrini, Anthony D. “Boys’ Rough-and-Tumble Play and Social Competence: Contemporaneous and Longitudinal Relations.” Pellegrini, Anthony D. (Ed.) The Future of Play Theory. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1995.

- Salen, Katie & Zimmerman, Eric. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2004.

- http://spoonful.com/family-fun/sports-athletic-games/tag-chase-games

- http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/580254/tag

- http://humansvszombies.org/